I get email alerts whenever anyone mentions jellyfish in a research article, and most of the time these alerts do not result in days of emotional confusion. But for almost two weeks I’ve been tiptoeing around this paper. Reading parts, feeling both angry and intrigued. Putting it down, and coming back to it later. It’s how I feel about Game of Thrones– do I hate it, love it? I’m just not sure. As a jelly biologist, my allegiance is with the jellies, always. However, I recognize they’re causing major problems around the world, clogging fishing nets and power plants, stinging people and ruining tourism. I get it, and it makes me sad. Starving babies and chemical polution also make me sad. This paper proposes a solution that could help solve all of these problems– it will help people eat, be organic and chemical free, and keeps jellies out of bays. All it requires is the saluter of thousands of jellyfish.

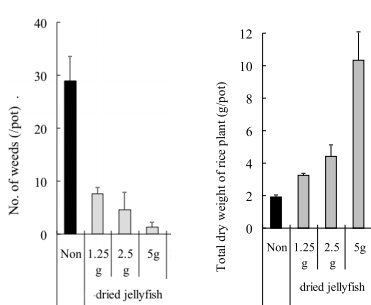

If we collect tons of jellies, de-salt and dry them, then mash them up into little bits and put them in soil, wouldn’t you know, rice grows better. In fact, jellyfish chips suppress weed growth and increase plant size, all without chemicals or fertilizers.

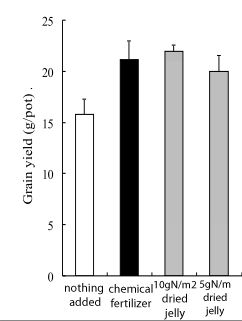

Not only is this solution great at getting rid of weeds and growing up big stalks of rice, but it also increases the harvest yield. With dried jellyfish farmers can grow as much rice as they can by using chemical fertilizers:

This is all great news for food production, and fans of organic farming practices, but really bad news if you’re a jellyfish. Jelly blooms are a natural part of the jelly life cycle, and without them jellies would be in trouble. But there’s a catch. When ecosystems are compromised by population or overfishing, some jelly species go nuts, taking over all the food and resources they used to share with fish. Like off the coast of Namibia, where overfishing has resulted in greater jellyfish biomass than fish biomass, numbers flipped from that of the pre-fishing ecosystem. In Japan (a country that loves its rice) giant jellies have been incredibly destructive to the fishing industry. And it’s not like many jellies make it alive out of these nets anyway.

If there is a way to curb jelly overpopulation in some areas, while also increasing food production, I guess I can’t argue. Places like Namibia may be able to benefit from their jellies, while rehabbing a damaged ecosystem at the same time. But it does break my heart a little to say that.

How do you de-salt a jellyfish?

Good question. I’m not sure. They don’t mention the source of jellies in the article, or how they were processed. Two things I’d very much like to know.

Thanks for the interesting article.

I will from now on look at jellyfish differently, less scared, more interested.

The article is fairly straightforward on the source; I guess it means wherever they are so abundant, that they are a ‘nuisance’ to human populations.

Processing : Is it simply dry them and powder the brittle mass ?

The only de-salt process that I can currently visualise seems unsustainable, just wash it in ‘plain’ water, till osmosis( reverse?) does it’s job……

I’m glad you enjoyed the article, and thank you for stopping by 🙂 Human/jelly relations are so complicated, what we find annoying may be perfectly normal for them. People often blame an increase in the number of jelly as a reason for concern, but I like to counter that there has been a huge increase in the number of *people* as well, and perhaps in many places there weren’t people to appreciate the large numbers of jellies before. For me, harvesting jellies only makes sense in areas where we know for sure they’ve increased. And especially when we know that increase is due to people. In other places we should proceed with more caution.

As for your question, I’ve never done it but I believe it’s fairly simple. I like your proposal of soaking jellies in freshwater. In places where there is a lot of rainfall (like Thailand) soaking jellies may be easy. And once they are dry, I guess you just mash them into chips. There is already a pretty active jelly food industry, where jellies are de-salted and wrapped up. You can check out this post for video and images of a jelly harvest: jellybiologist.com/2013/03/11/jellyfish-video-what-do-jellyfish-taste-like

I’m not quite sure how this whole invasion of jellyfish happened, what other species do you think could be affected by this and grow even more? And is Japan right now the main problem with the jellyfish?

We’re seeing variable jelly numbers all over, but it’s not clear that there is an “invasion” going on in most of these places. A lot of it, I suspect, has to do with the increasing extent to which humans are entering their world. The more we use jelly habitat (for fish farming, plant cooling etc) the more we’ll be impacted by them (and them by us!).

What about feeding the jellies to farmed fish and shrimp? That protein can be processed into commercial fish chows. It’s a lot better than feeding them corn grown on land. I know there are problems with fish farming but, to whatever extent we pursue it, feed the Nomuras!

I haven’t heard of anyone trying this, but it’s an interesting idea. Do you know of any?